As part of a another current project, which I will have more to say about…

MMT and Power – Part 1

I often read that Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is defective because it has no theory of power relations. Some critics link this in their narrative to their claim that MMT also has no theory of inflation. They then proceed to attack concepts such as employment buffers, on the grounds, that MMT cannot propose a solution to inflation if it has no understanding of how power relations cause inflation. These criticisms don’t come from the conservative side of the policy debate but rather from the so-called Left, although I wonder just how ‘left’ some of the commentators who cast these aspersions actually are. The problem with these criticisms is that they have clearly adopted a partial approach to their understanding of what MMT is, presumably through not reading the literature widely enough, but also because of the way, some MMT proponents choose to represent our work. In this two part series, I propose to interrogate this issue and demonstrate that power and class is central to any contribution I have made to the development of the MMT literature. Part 1 sets the context and illustrates why some people might be confused.

Interesting historical trends

The first thing to think about is the way that economics has evolved over the last few centuries.

When I started studying economics I wanted to be thought of as a student of political economy.

I was also studying philosophy, history, mathematics, statistics, political science and had an interest in sociology and anthropology.

Over the course of my studies I had to make decisions like everyone, but I sought to pack as many electives in as possible and I actually ended up with more points than were necessary to gain the qualifications sought, because I could never quite come to terms with narrowing too much.

The first political economists were the French – Physiocrats – who emerged during the – Age of Enlightenment.

Scholars such as – François Quesnay – and – Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot – were at the forefront of this approach which shifted the focus of national wealth from trade, which had been the focus of the mercantilists, to production and the contribution of labour as a source of value.

They also promoted the dominance of the agricultural sector as a source of economic development. To some extent, they influenced the later ideas of Henry George on land value taxation.

They also spawned the link between liberalism and economics advocating laissez-faire approaches from government, who had responsibility for maintaining property rights.

They were followed by the major British classical economists – Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill who advanced the discussion by focusing on how production and trade interacted with social norms and government policy with an emphasis on distributional aspects (income and wealth).

At this point, ‘economics’ really was an extension of – moral philosophy – and it was clear that a study of economics had to consider social institutions, which included who could exercise power over production and distribution.

Marx, of course, ground his analysis, in the power that the capital-owning class had over the rest of the population, by dint of the necessity to work to survive.

His analysis considered the socio-economic dynamics that followed from the exercise of that power.

So historically, political economy was concerned, rather explicitly with social classes, power struggles, custom and law, and economic outcomes.

As I have written about before, the growing interest in Marxism in the mid-19th century and the threat that this posed the elites of the burgeoning industrial society required a response.

The – Revolutions of 1848 – which were mostly a challenge to the existing monarchial dynasties, also were driven by working class concerns that they were being exploited by owners of capital.

This was particularly the case for urban working class activism who were the day labourers and factory workers and faced massive declines in their real wages interspersed with chronic unemployment.

Marxism became very appealing.

The – Paris Commune – in 1871, was a further expression of the rise of working class activism, which threatened the status quo.

One of the responses was the development of neoclassical economics – the so-called Marginal revolution, which saw – William Stanley Jevons – shift the emphasis of economic studies to a more mathematical approach in his 1879 book and – Alfred Marshall – publish his famous book in 1890.

This shift marked the beginning of the modern approach to economic problems and the terminology shifted from ‘political economy’ to ‘economics’, which was no small shift confined to nomenclature.

It marked a narrowing of focus consistent with a view that ‘individualism’ dominated and any ‘market power’ (concentration, monopoly, trade unions, etc) were ephemeral phenonema, in many cases, created by errant government policy.

The story went that if government’s allowed the free market to work and concentrated on enforcing private property rights, so that free contract could operate smoothly, then these ‘power’ sources would evaporate.

Increasingly, the concept of class was abandoned as an organising framework, and individual human behaviour was reduced to a series of a priori statements that were amenable to solutions using the available mathematics.

Mathematical technique and its limitations in this context became dominant in the design of the problem, by which I mean, that complex interactions in society were abstracted from and the resulting ‘models’ were so simple that they had no application to the real world.

And that sort of self-fulfilling activity became embedded in the profession.

I discussed that issue in these blog posts (among others):

1. The evidence from the sociologists against economic thinking is compelling (November 19, 2019).

2. How social democratic parties erect the plank and then walk it – Part 1 (June 6, 2019).

A substantial portion of my profession, go to graduate school, receive the heavy indoctrination from their masters, are awarded their PhD degrees, access an academic teaching job, entertain visits from publishers who adorn them with the latest macro economics textbook and all the related teaching materials (slideshows, quizzes, et cetera), and then, essentially, go to sleep!

They teach year in and year out from these textbooks. Some publish ‘haiku-type’ papers which provide no knowledge about the real world, but earned them plaudits from the Academy and, hence, promotion, higher salaries, more status, and a better retirement.

But they learn early on not to question the main parameters of their discipline. The indoctrination in graduate programs is very effective and it is far more simpler to go to sleep and enjoy the rewards that a highly-paid and secure profession brings.

They teach a fiction.

More insidious is that neo-liberal economics privileges the interests of capital and the financial elites.

Power is maintained.

To understand why there is so much resistance to abandoning failed economic theories, we need to understand that the mainstream economics paradigm is much more than a set of theories that economics professors indoctrinate their students with.

In his Op Ed (January 13, 2017) – Why we need political economy – Mark Robbins writes:

The principal shortcoming of economic analysis, as the argument goes, is that it presumes a separation of economy and politics that does not meaningfully represent reality. This is in contrast to political economy … which assumes that politics and economics are fundamentally inseparable and that the relationship between states and markets is key to a rounded comprehension of the world …

The assumed separation of politics and economics is very much a 20th-century phenomenon …

Even the central organising concept of the ‘free market’ is an imaginary construct that has no existence in reality. All markets require legal frameworks – government laws, rules of contract, etc.

I consulted – Google Ngram Viewer – which “charts the frequencies of any set of search strings using a yearly count of n-grams found in sources printed between 1500 and 2019” to demonstrate the historical context in which terms in my discipline have been used.

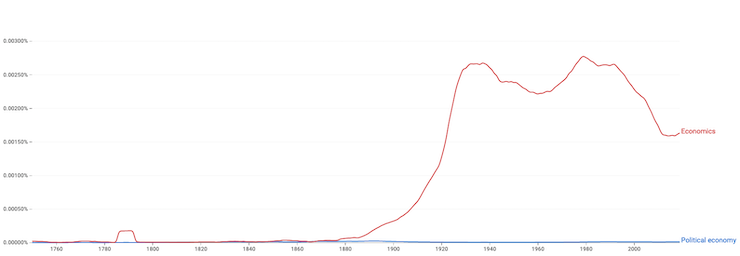

Here is a Ngram graph for the keyword – Political Economy – from 1750 to 2019.

The graph peaks around 1890 (the horizontal axis is marked in periods of 20 years), which just happens to coincide with the release of Marshall’s Principles.

The next Ngram graph is for the keywords – Political economy and Economics.

The juxtaposition of the term “Economics” (red line) with “Political Economy” (the blue line that you can barely see as it traces the horizontal axis) really demonstrates the shift in emphasis.

By 1900, or so very few people referred to the way we study the economy as ‘political economy’, and that term became the domain of those pursuing more heterodox approaches (Marxists, institutionalists, etc) or the public choice theorists, who were still operating within the ‘free market’ individualistic framework.

The other big shift was the development of macroeconomics in the 1930s as a separate field of study within ‘economics’.

Prior to the 1930s, there was no separate field of study called macroeconomics.

The dominant neoclassical school of thought in economics at the time considered that to make statements about the economy as a whole (the domain of macroeconomics) one could just infer from reasoning conducted at the individual unit or atomistic level.

This reasoning was rejected in the 1930s, and macroeconomics became a separate discipline precisely because the dominant way of thinking at the time, blithely transposing microeconomic truisms to the macro scale, was riddled with errors of logic that led to spurious analytical reasoning and poor policy advice.

Microeconomics develops theories about individual behavioural units in the economy – at the level of the person, household, or firm.

For example, it might seek to explain the employment decisions of a firm or the saving decisions of an individual income recipient.

However, microeconomic theory ignores knock-on effects on others when examining these firm- or household-level decisions.

That is clearly inappropriate if we look at the macroeconomy, where we must consider these wider impacts.

During the Great Depression, British economist John Maynard Keynes and others considered that by ignoring these interdependencies (knock-on effects), economists were creating a compositional fallacy.

I elaborate more on that issue in this blog post (among others) – Fiscal austerity – the newest fallacy of composition (July 6, 2010).

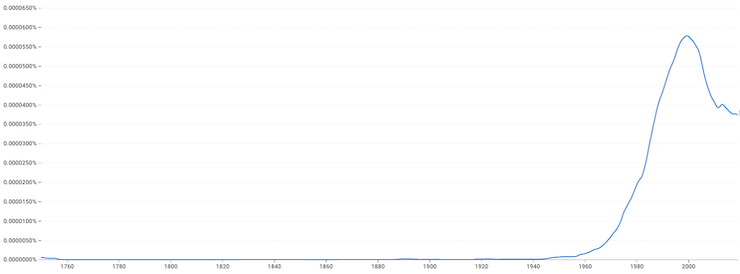

The macroeconomics graph starts to rise in the late 1930s.

Here is a Ngram graph for the keyword – Macroeconomics:

But the mainstream profession is still dominated by neoclassical thinking, even the ‘New Keynesian’ macroeconomists construct their framework on microeconomic principles.

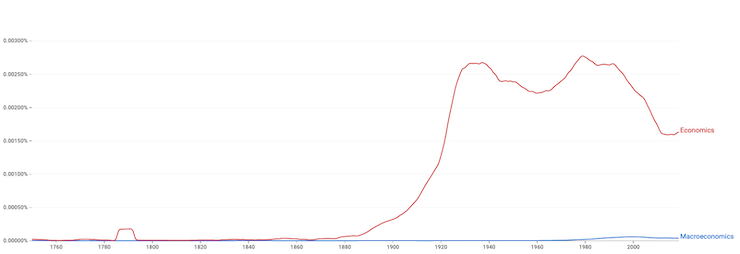

This leads to the the relativities shown in the next Ngram graph for the keywords – Economics and Macroeconomics:

So the first thing to understand is that MMT contains a coherent logic that will teach you to resist falling into intuitive traps and compositional fallacies and teaches you to think in a macroeconomic way.

It is ground in the early insights that led Keynes and others to create macroeconomics as a separate discipline within ‘economics’.

MMT economists reject the individualism of neoclassical marginalism.

They place a priority on understanding the institutional context within which economic outcomes are generated.

That means they understand that power relations that are embedded in these institutional structures are central to understanding the way the monetary system operates and the capacities of government, as the currency-issuer.

MMT ignores the link between money and the real economy

In one article a few years ago (February 21, 2019) – Modern Monetary Theory Isn’t Helping – Doug Henwood, apart from seeming to be settling some personal scores, which are beyond my interest or specific knowledge, introduced this ‘power vacuum’ critique of MMT.

He wrote:

MMTers show a strange lack of interest in the specificity of capitalism – how production and distribution are organized, how demand for credit arises in the course of commerce, how people earn their living and under what conditions – and their rejection of earlier PK work on money renders nearly invisible any link between money and things or money and people (or people and things via money). Marx said a man carries his bond with society in his pocket, a recognition that money is one of our principal modes of social organization and control. Or, as Antonio Negri put it in one of his more lucid moments, money has only one face, that of the boss. If you don’t work and do as you’re told, you go broke and starve.

Through the fantasy of effortless keystroke money, all those relations of necessity and power supposedly get wiped away. But it’s not some imposed scarcity of money itself that produces those relations.

MMT’s lack of interest in the relationship between money and the real economy causes adherents to overlook the connection between taxing, spending, and the allocation of resources. We have homeless people living on the streets of San Francisco blocks from Twitter and Uber’s headquarters, bridges collapsing, trains derailing, schools falling to bits – the entire structure of private opulence and public squalor, as John Kenneth Galbraith put it long ago, because the public sector is starved for resources. Taxing takes those resources out of private hands and puts them into public ones, with at least the potential for them to be spent on more humane pursuits. Fewer Lamborghinis, more bullet trains. Fewer Hamptons houses, more public housing.

Enacting single payer, for example, isn’t just a matter of a few billion extra keystrokes. It means dismantling the absurd administrative apparatus of the US health care system, shifting premiums for private insurance into public expenditures, transforming the price-gouging business model of the drug industry, and taking care of workers displaced by the renovation.

If we take out the reference to MMT, then what Doug Henwood is demonstrating is the lurid lack of ethics that defines the modern economic system.

But to then introduce that as an attack on MMT is to advance a claim that is is something like, if you don’t have a theory of everything, then what you do offer is problematic.

Apparently, Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) is defective because it doesn’t have a theory of the state, or under-theorises public power, or excludes considerations of gender, ethnicity, sexuality, and more.

Apparently, we don’t advance theories of why the distribution of income allows Twitter to coexist with those who do not have homes.

Now, before the flame throwers are primed, make sure that you read me ‘saying’ that all of these things that MMT apparently excludes are obviously important and deserve intellectual enquiry from those who have the appropriate research skills and background (literature, methods, training etc).

That is why universities have many departments (disciplines) because not everyone has all the appropriate research skills (and interest) to do everything.

It is a flawed critique that says that MMT can never be accepted by the Left, for example, because we have not presented a theory of the state.

To say there is a “lack of interest” in the consequences of “money and the “real economy” is flagrantly false.

A central concern of macroeconomics, the way that MMT develops it, is to understand the consequences of the use of money (as the unit of account) in transactions that link expenditure to production (real economy) to income generation and to employment (real economy).

A major influence on the way we have developed MMT is Abba Lerner’s functional finance.

Please read – Functional finance and modern monetary theory (November 1, 2009) – for more detail.

Functional finance is about the outcomes of government policy decisions explicitly linking its currency capacity to the real economy.

The MMT economists have almost single-handedly attacked the obsession with financial aggregates (nominal size of deficits, deficit to GDP ratios, public debt to GDP ratios) in the modern era and continually tried to refocus the debate onto the real economy.

Even many other heterodox economists who oppose the mainstream still lapse into the ‘sound finance’ frames – ‘tax the rich’, ‘Robin Hood taxes’, ‘okay for government to borrow when interest rates are low’, and all the rest of them.

In incorporating the functional approach, one of the central aims of the MMT literature has been to reinstate full employment as a key objective of government after decades of policy being driven by NAIRU logic.

We are the only economists who juxtapose employment and unemployment buffer stocks in the discussion of inflation.

That explicitly links the real economy (employment and unemployment) to the nominal economy (inflation, money).

So Henwood was just plain wrong in that regard.

But this is the point.

MMT provides an impeccable explanation for mass unemployment and shows what the fiscal position has to be to ensure there is full employment.

That is it links money and the real economy at the macroeconomic level, which is what a good macroeconomics should do.

But the implications of the mass unemployment – the family damage, the likelihood of increased alcohol and substance abuse, the likelihood of increased participation in the justice system, the social alienation, and all the other pathologies that accompany joblessness – are the realms of sociology, psychology, legal studies, etc.

Macroeconomists do macroeconomics.

We show why there is unemployment.

MMT is not a framework for studying the impacts of social alienation arising from that unemployment.

Conclusion

In Part 2 we will discuss the ‘tax the rich’ story as an extension of the discussion just provided.

We will also question the ‘MMT is a lens’ proposal and see why I introduced that sort of framing, the limitations to it, and where we can take it – straight to power relations in a capitalist society.

That is enough for today!

(c) Copyright 2021 William Mitchell. All Rights Reserved.

Morning Bill,

Fred Lee

I’ve been reading some of his papers recently which I find very interesting. Well worth a mention here as he believed micro and macro should never have been different subjects and studied together to get a better picture of the economy as a whole.

Then he went on to say. When you study both Macro and Micro you have to look at what the neoclassicals say and study that. Basically work twice as hard as everyone else but become a better economist. Build better models that link the two that reflect reality rather than fantasy.

“it was claer that a study of economics ”

Typo.

Dear Derek Henry (at 2021/05/06 at 5:19 pm)

There is very little in mainstream neoclassical microeconomics that is worth the time taken to read it.

Micro studies like those of Edwards, Weiskopf and Gordon and Katherine Stone, for example, are very enlightening but not what we usually refer to as microeconomics.

best wishes

bill

To me, MMT is about the truth.

And that is enough for me to keep defending it.

Mainstream economics is not about facts, but rather about some sort of bedtime stories, to keep the masses asleep, while the elites ransack the loot.

Therefore, mainstream economics is an instrument of class dominance, of the elites over the masses.

That fact implies that any challanging theory will be automatically labled in the opposite side of the class struggle warfare.

The “power relations” talk is nothing more than ways of upholding elite dominance.

One might be sympathetic with the elites and believe in the trickle down trope and other bogus claims (like central bank independence, for example).

In fact, many of us are (that’s the reason why fascists keep beeing elected all over the world).

Or, one might see trickle down economics as the crumbs that fall off the rich man’s table.

Whether we accept the truth or not, is our exclusive choice.

But remember: profit seeking is destroying the planet, so maybe we should look after the truth after all.

Thank you for this post Bill. I look forward to the next one.

MMT is required for understanding the true constraints we face in our societies, resources broadly defined, not finance. Thank you Bill, and the other developers of MMT, for that critical analysis.

However understanding the true constraints is only the first step in getting our societies to become more just. The need to overcome the power of those who benefit from current social and economic arrangements remains.

Probably the most egregious example is the US healthcare system. Its costs are about double per capita of those in other developed countries. A proper public system would save about $1.5 trillion annually and allow that value of resources to be allocated elsewhere. MMT is not necessary for that fight. The obstacle to reform is the beneficiaries of the current US system (pharma, insurance, for-profit hospitals, highly paid doctors). They won’t give up that huge amount of money without a fight. No fight, no change.

Unfortunately many consumers of MMT ideas expect too much. This was especially on view at the MMT conference in New York three (?) years ago. MMT insights are very empowering so I understand the enthusiasm of activists and others new to the analysis. Unfortunately only knowing we are not limited by finance won’t get us from where we are today to a more just society. That is the job of activists on the ground and their allies in political parties (if any).

Bill, does Henwood think bridges are collapsing because the private sector hired away all of the engineers and none are left for the government to pay to fix the bridges?

Looking at economics as a designer I have always seen it a bit differently. I will start with my favourite definition of design: “thoughts and actions intended to change thoughts and actions” (John Christopher Jones, 2002); then whizz very briefly through just enough design theory for you to understand what on earth I am on about:

– Everything is designed. Design is part of the human condition and we are all doing it constantly. No other organism (that we know of) has this ability to design both their surroundings and their own thoughts in the way we do. It is how we arrange the flowers, where we choose to stand to frame our view from a mountain, the order in which we sort our task list, the words we choose to frame an argument. These are all design decisions.

– Design, by definition, has intent.

– Design draws on culture, and contributes to culture – a new design is always created in the context of previous designs, and itself adds to the context for future designs.

– These are always unintended consequences. Designer/s use their knowledge experience to plan outcomes, but can never know every possible result and cannot control how others will see and use the design.

There is a game designers like to play – post rationalise the design intent by observing and using the finished product. For simple objects with no context this can be quite fun. Imagine a bunch of designers standing around at a trade fair post-rationalising a floor lamp. We can easily determine that the lamp is intended to cast light a certain way, to dominate or recede in a space, we can even go as far as to guess the cultural memories intended to be triggered by the aesthetic.

When we have more context, such as the story behind the design or the designer, or if the design is more complex and has more observable results, then we can have more certainty in our assessment of intent.

Something all designers experience is unintended or undesirable results. While a few are bold enough to claim it was meant to be that way, most of us will revise the design to better achieve the intent. The product will be “pulled from the shelves” and re-launched, or if it’s especially bad it may be scrapped altogether.

The economy, and the economic models and theories that support it, are all designed. The intent of the designers is reasonably evident in the outcomes. Further context is provided by knowing about the designers of these models. We can even directly know some of their intent, both from contemporaneous documents and from their own publications (a future line of research for me…).

However, for the purposes of a blog comment a quick post-rationalisation of the design intent can tell us with reasonable certainty the following:

– With 50 odd years of observed results from the neoliberal experiment, the fact that the designers have not revised the design of neoliberalism in this time indicates that the observed results are intended.

– The beneficiaries of this design must have had a hand in creating and maintaining the design. They may not have the expertise to design it themselves, but they certainly pay economists who do. Professional designers do not work for free.

– The cultural impacts of this design are manifest.

I thank Bill for teaching the basics of MMT in a way that someone from another discipline can understand it. If MMT is a lens, the vision it has given me is a different way of seeing economics – and different ways of seeing is exactly what designers use to understand users and context.

What is most insidious about neo-liberal / classical economics is the way it has infected our culture and changed our perspective. With its heady mix of individualism, consumerism, and competition, people believe the facts they are told about “the economy” even while they think economics is bullshit!

When people are resigned to the fact that the economy just is, the way neoliberalism has conditioned us all to do, and rich people will just get richer, they will be complacent. But when people see that the economy is designed to make them poorer and a few very rich, and that those very rich deliberately designed it to be this way, maybe then people will be willing see a different reality.

As Nietzsche might have said, our perspective is changing the facts.

The facts, as presented by self-interested corporate media commentators and well paid lobbyists, no longer align with the lived experience of many readers. People are disgruntled. But none so far have painted the vision that allows people to see the designers of their situation, to reveal the little man behind the curtain.

Some politicians have begun to notice this but so far it is only the ratbags. The missing link for MMT and political economy right now is the political. We need politicians with both the knowledge and skill to sell this vision to people like my mum.

Design definitions:

– “Everyone designs who devises courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones” (Herbert Simon, 1969)

– John Heskett reverses my viewpoint – regarding design from the perspective of an economist – and in 2005 came up with this definition: “design is to design a design to produce a design” (his book Design and the Creation of Value is what got me into all this)

-My favourite and most fundamental definition of design is from John Christopher Jones in 2002: “thoughts and actions intended to change thoughts and actions”

What a great comment Bradley Schott.

“But when people see that the economy is designed to make them poorer and a few very rich, and that those very rich deliberately designed it to be this way, maybe then people will be willing see a different reality.”

That’s the way I’ve come to view it- but I never put it as well as that.

I also love “As Nietzsche might have said” just because it reminds me of a happy time. One year at UConn, the state university I went to, they ran out of housing for students and they kind of randomly assigned a bunch of us to tiny off campus 2 bedroom apartments designed for their graduate students who might have a spouse and a child. So six of us who did not know each other at all ended up sharing maybe a 500 sq. ft. apartment. And we had some great discussions and arguments about all kinds of things. And one of us was a philosophy major who almost invariably would interject at some point in the argument- ‘Well, as Nietzsche said’- and then something that Nietzsche might have said. It became amazing to the rest of us (who knew nothing about Nietzsche) all the things Nietzsche said and how applicable they were to discussions among college roommates in the 1980’s. I was a bit disappointed when I actually read some of what Nietzsche wrote- but more impressed with my roommate Eric- the philosopher who could apparently interpret Nietzsche on the fly to buttress any argument.

And what a difficult name to try and spell- was always trying to find out who Neechee was.

Mainstream macroeconomics is so detached from reality that has well entered the realm of absurdity a long time ago. I remember as a graduate student of economics, an article on labor market by Princeton professor Gregory Chow employing optimal control theory’s “brachistochrone” problem in designing the best policy to solve the unemployment problem! His approach was a direct application of ballistic theory in physics, in which the trajectory of a missile is designed to hit a moving target in the shortest possible time! And we had to struggle with such nonsense because if you didn’t pass the exam that would have been the end of your studies.

Now, a simple comparison of the brachistochrone with the Job Guarantee is very illuminating.

Optimal Control Theory is another of those mathematical addictions that tend to fall apart when they come up against the real world.

Here’s Brian Romanachuk on the subject and with which I concur wholeheartedly:

“When I was a doctoral student of Control Systems Engineering in the early 1990’s, optimal control had been abandoned as a failure almost a generation earlier by engineers (late 1960’s – mid 1970’s).

[…] when applied to real world engineering systems, optimal control rules had a distressing tendency to cause systems to be physically destroyed.”

I am very interested in how power fits in the MMT description of how the economy works. I have always thought that the more regular crap economics I was taught completely skipped just about all issues of differing power and how that influenced economic relationships long before I heard of MMT.

So I have read part one several times carefully as I can and am now going to relate what I understand and don’t understand about it in the hope that where I am confused or mistaken will become clear in part 2 or in comments. So here goes

I don’t really understand the opening paragraph about power and inflation-so that’s not a good start.

Slightly after it becomes clear to me that Bill was a much better student than I at economics and that when he realized what they were teaching him was bullshit, well he was going to correct them by coming up with something better.

Marx- Marx ground his analysis (maybe with a pepper grinder?) into some gun powder that clearly delineated power structures between labor and capital. Whatever he used to grind it, the result was more than potentially explosive and the capitalist tools had to come up with some response even if it was very lame.

And that response was the whole marginal revolutional mathematically intensive garbage I was taught.

Or maybe not- because Keynes made a distinction that mattered between macro and micro economics- and they taught me about Keynes for sure. And Keynes intertwined with Institutionalism gives a better understanding of power structures whatever that means.

Then there is a bit about a dopey MMT critic, which I get completely, but has nothing to do with power.

Then there is the conclusion and that is it till part 2.

\

So I am left not overly awed about MMT explanations of power and how that is part of economics at this point. Maybe part 2 will really drive home the power differential between workers and employers? The power the government has? The additional power that comes from issuing the currency?

@Jerry Brown: ”The power the government has? The additional power that comes from issuing the currency?”

In the past MMT has mostly focused on the mechanics of the monetary-fiscal system to counter the very effective propaganda obstacle to getting progressive public policy done, that being governments are like households, too much debt is bad, etc. An inference pointed out was that we don’t need the money of the rich to do good things, that the government can fund anything it wants in its own currency, and that critical services don’t need to be turned over to the for-profit sector. That’s the functional finance part of MMT and it is very empowering for those who want governments to fund more non-profit services.

MMT also focused on the very liberating idea that anyone who wants a job should be offered one by the state. That’s the Job Guarantee part.

Bill has often pointed out that MMT is a lens we can use to look at the economy. The political and power reality is that while functional finance can be used for good it can also be used to fund a vast military-industrial-surveillance-thinktank complex with soldiers and military bases around the world that discipline any country that is disobedient to the dominant power. It can also do both – good at home, bad overseas (social imperialism).

I too am looking forward to Bill”s next blog post on the topic but am not sure what answer to your questions you are expecting.

Well Keith, as Nietzsche might have said (but almost certainly didn’t), people who ask questions often get surprised by the answers they are given. Well, maybe he said that- who knows 😉

well hopefully a set up blog for part 2.

Apart from an assertion of politics.

No description of power or inflation yet.

A major point in your article: that politics and economics cannot be separated – valid enough.

However, the question then is: if politics and economics cannot be separated, why is it at all surprising that neoliberal economics has such sway?

Is that not a validation that politics drives mainstream economics?

Similarly – in the era when capitalists/industrialists were striving against entrenched feudal interests: is this not yet another example where convenient economic theories are pushed by well funded interests for their own benefit, regardless of the economists’ own views and goals?

The profession of economics existing primarily to provide credence to well backed factions would explain a lot of why the profession has so little skill in predicting/producing real world outcomes.

I’ve read little of this particular blog but do have this to say in relation to power. It is a quote from Wray, I think from Understanding Modern Money

https://twitter.com/AusMMT/status/1337242516681183234?s=20

A red flag for me (no pun intended, but not a bad one) is, how odd that it is that via MMT I came to precisely the understanding that Henwood attributes to Marx, and which he sees as a deficiency of MMT.

“Marx said a man carries his bond with society in his pocket, a recognition that money is one of our principal modes of social organization and control.”

Does Henwood appreciate the depth of the creative tension between “organization” and “control”? (I think about the Buddhist concept of “milk debt”.)

I now think of money as a universal measure of IOUs. Via MMT we can contrast monetary systems with kinship systems and the function of obligations or debts to bind social action in those systems. This is just one part of the impact MMT has had on my world view.

Doug Henwood is not a serious critic. He is just bitter than other people’s theories are more accurate, useful, and relevant than his.

I find it amusing whenever mainstream people like Mr. Henwood actually talks about real economy and people’s lives. Its also funny when they accuse MMT of being fantasy. Their own track record has been so bankrupt, one cannot help but laugh at it.

How does MMT even say we should ignore power relations? Hasn’t Marx worked that out? Whats wrong with combining MMT and Marx when situation demands? When situation demands, as in MMT, in order for a student to pick up the ideas, we simplify it by ignoring power relations but even outright reject it as Henwood alleges.

Political economy is a difficult subject because it has many moving parts. Some play huge role in certain situations.

Then there are monetary facts, which MMT presents. MMT has its own stuff to say, so one should use it when talking about policies and spending. When one goes out and organize, she should use Marx instead.

MMT can always be used to smash the “how are you going to pay for it” arguments.

What does Henwood even understand about power relations? He talks as if government really would implement a policy when the policy would help the masses but wipe out the oppressors’ livelihood. Mr. Power relations talks like a regular liberal when he implies that “we” (???) can implement policies.

Finally, who are these simpletons that Henwood allege who do not understand that a person can/should learn even more beyond MMT’s basic tenets? Does Mr Henwood think that social change is possible without the most arduous and painstaking investment of time and energy on the part of working class?

but never* outright reject it as Henwood alleges.

Henwood’s comments come across as someone pointlessly angry about the fact that the inventors of a new electron microscope haven’t at the same time set out a public health program for preventing or curing disease.